CRLN signed onto a letter to the State Department calling for systemic reform of Colombia’s military intelligence

May 22, 2020

Acting Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Ambassador Michael Kozak U.S. Ambassador to Colombia Ambassador Philip S. Goldberg U.S. Department of State and U.S. Embassy to Colombia, Bogota

Dear Ambassador Kozak and Ambassador Goldberg,

We write out of deep concern, which we are confident you share, regarding the revelations that Colombian Army intelligence units compiled detailed dossiers on the personal lives and activities of at least 130 reporters, human rights defenders, politicians, judges, union leaders, and possible military whistleblowers. As you know, the group contained U.S. citizens, including several reporters and a Colombian senator.

This scandal is disturbing in itself and for what it says about Colombia’s inability to reform its military and intelligence services. In 1998, the 20th Military Intelligence Brigade was disbanded due to charges that it had been involved in the 1995 murder of Conservative Senator Álvaro Gómez Hurtado and his aide and, according to the 1997 State Department human rights report, targeted killings and forced disappearances. In 2011, the Administrative Security Department (DAS), Colombia’s main intelligence service, was disbanded due to the massive surveillance, as well as threats against, human rights defenders, opposition politicians, Supreme Court judges, and reporters. In 2014, Semana magazine revealed army intelligence was spying on peace accord negotiators in the so-called Operation Andromeda. In 2019, Semana exposed another surveillance campaign using “Invisible Man” and “Stingray” equipment against Supreme Court justices, opposition politicians, and U.S. and Colombian reporters, including its own journalists. In March 2020, a Twitter list compiled by the Colombian army identified the accounts of journalists, human rights advocates, and Colombia’s Truth Commission and Special Jurisdiction for Peace as “opposition” accounts.

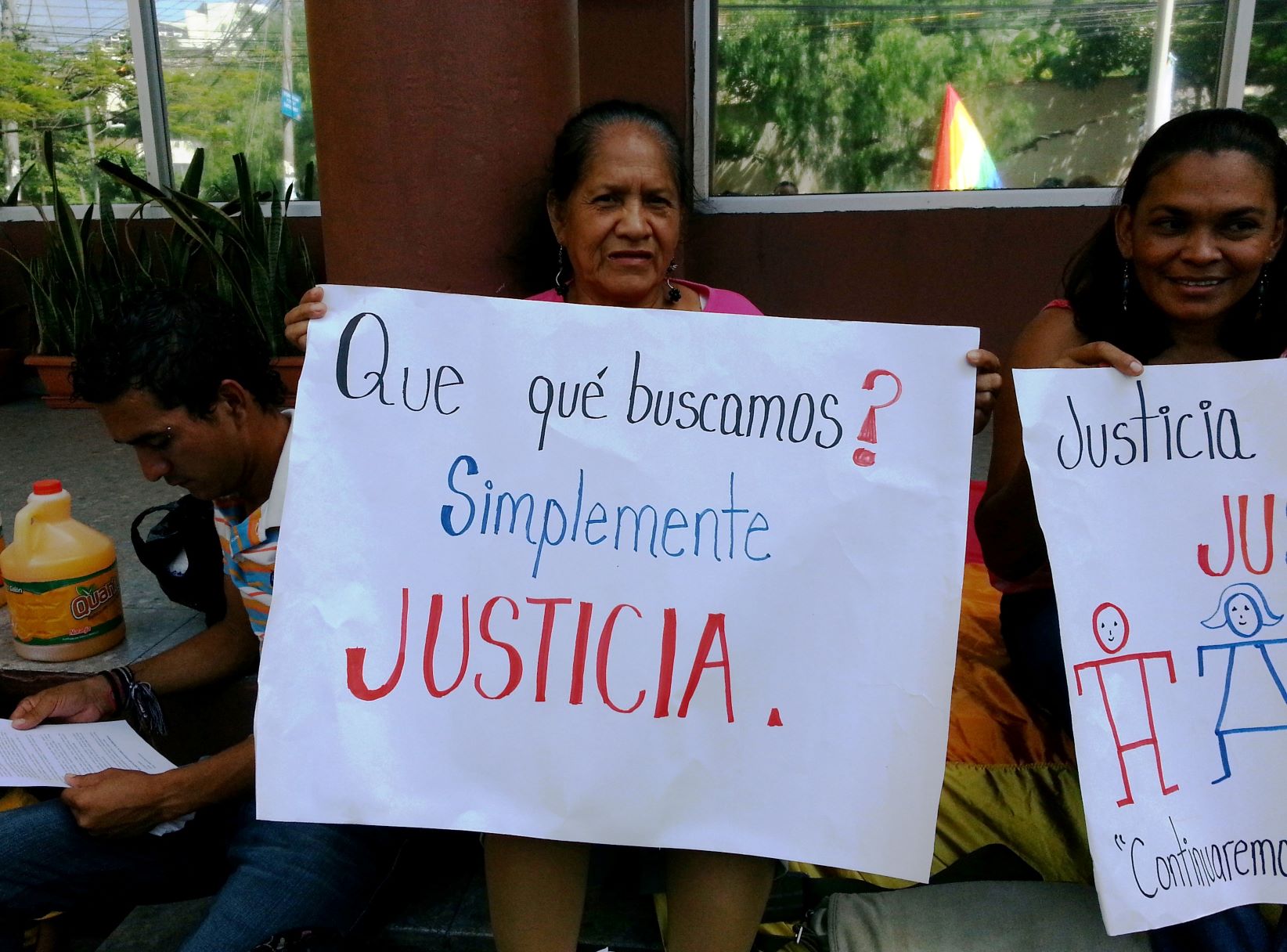

The surveillance is far worse than a massive invasion of privacy. The targeting of political opposition, judicial personnel, human rights defenders, and journalists leads to threats, attacks, and killings. For example, during the 2019 surveillance operation, Semana reporters and their family members received funeral wreaths, prayer cards, and a tombstone. This surveillance and targeting has a chilling effect on the very people and institutions needed to maintain a vibrant democracy. It means that no amount of government protection programs can stop the targeted killing of human rights defenders and social leaders. The persistence of this kind of surveillance suggests that an important segment of Colombia’s military and intelligence services – and of the political class – fail to appreciate the fundamental role of a free press, human rights and other civil society organizations, and peaceful dissent in any vibrant democracy.

We are also deeply concerned to hear that some U.S. intelligence equipment may have been used for these illegal efforts. Semana “confirmed with U.S. embassy sources that the Americans recovered from several military units the tactical monitoring and location equipment that it had lent them.”

As we review this latest manifestation of Colombia’s deeply rooted problem of identifying as enemies and persecuting those who wish to defend human rights, uphold justice, and report the truth, we ask ourselves: What can ensure that this never happens again?

At a minimum, we recommend that the U.S. government:

• Support the creation of an independent group of experts under the auspices of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to investigate and recommend steps to achieve justice and non-repetition.

• Press for a thorough review of military doctrine and training to ensure that it promotes a proper understanding of the role of the military in a democratic society, including the role of human rights defenders, journalists, opposition politicians, and an independent judiciary. While the written doctrine was revised during the Santos Administration, clearly improvements to doctrine are not being followed. The review should seek an accounting for the too-frequent episodes of senior military behavior that contradicts this revised doctrine. Such a review must have input from Colombian human rights defenders and judicial experts, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

• Urge the Colombian government to provide all necessary protection measures, agreed upon with the targeted individuals and organizations, to ensure their physical and psychological integrity, as well as that of those around them. • Urge the Colombian government to purge all intelligence files, whether of state security forces or other organizations, collected on human rights organizations, finally addressing the long-standing demand by human rights organizations, unfulfilled for nearly a quarter century.

• Urge the Colombian government to reveal publicly the full extent of illegal intelligence operations targeting civil society activists, politicians, judges, and journalists, clarifying who was in charge, to whom they reported, what kind of intelligence was carried out, and with what objectives.

• The administration should direct DNI, CIA, NSA and DIA to inform congressional intelligence, armed services and foreign relations and foreign affairs committees of their conclusions on the full extent of illegal Colombian intelligence operations, clarifying who was in charge, to whom they reported, what kind of intelligence was carried out, and with what objectives. The administration should direct the same agencies to inform these congressional committees whether and when the U.S. government learned of these actions by the Colombian military and intelligence services and whether U.S. intelligence agencies cooperated with their counterparts even after learning of those actions.

• Investigate whether recipients of U.S. training and/or equipment participated in ordering or implementing these illegal activities and immediately suspend individuals and units involved from receiving U.S. training and equipment, per the Leahy Law.

• Suspend all U.S. support for Colombia’s military and intelligence services if the Colombian government does not immediately suspend and promptly investigate and prosecute officials who ordered and executed these illegal activities and conduct the thorough review and rewriting of military doctrine and training mentioned above.

If the nation is to realize the vision of so many Colombians to create a truly “post-conflict” society with shared prosperity under the rule of law, then intelligence targeting and surveillance of democratic actors must finally end. Thank you for your efforts to ensure Colombia turns the page for once and for all on these deadly, illegal, and anti-democratic activities.

Sincerely,

Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL)

Chicago Religious Leadership Network on Latin America (CRLN)

Colombia Grassroots Support, New Jersey

Colombia Human Rights Committee, Washington DC

Colombian Studies Group, Graduate Center – College University of New York

Colombian Studies Group, The New School International Institute on Race, Equality and Human Rights

Latin America Working Group (LAWG)

Network in Solidarity with the People of Guatemala (NISGUA)

Oxfam America

Presbyterian Peace Fellowship

School of the Americas Watch

United Church of Christ, Justice and Witness Ministries

Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA)

Witness for Peace Solidarity Collective