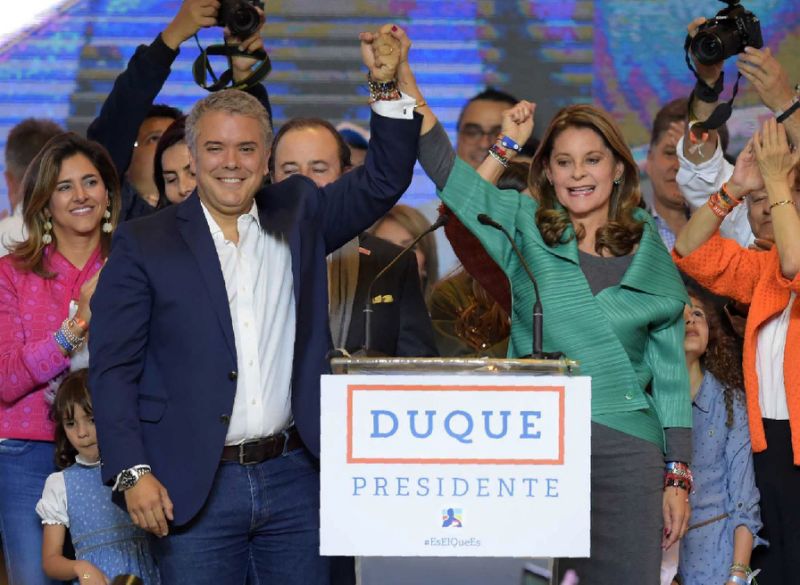

As someone who ran on a platform that was vehemently opposed to the Peace Accord agreed upon between Juan Manuel Santos and the FARC, Ivan Duque presents a challenge to the future of peace in Colombia.

It is unlikely that Duque will uphold or implement many of the aspects of the Peace Accord. The Constitutional Courts of Colombia have already reviewed the Peace Accord and made it clear that the Accord is law and must be upheld by the next three presidents, as the Accord envisions a 15-year implementation period. Despite this, it is still possible for Duque to take such slow measures in implementing the accord that there will be no progress at all during his presidency.

Although Duque has presented the Peace Accord as nothing more than a get-out-of-jail free card for ex-FARC members, in reality, the Accord offers a far-reaching opportunity for Colombia to develop into a more equitable and modern country. Many of the elements of the Accord focus on rural reform in the countryside and increasing educational opportunities and participation in government and politics among all Colombians.

While it is true that there are elements of the Accord that offer relatively lenient punishments to ex-combatants, such as the Special Jurisdiction for Peace that offers a means to avoid jail time, it is also true that this mechanism is largely responsible for preventing more than 7,000 combatants from disappearing and remobilizing.

Rural Reform

The rural reforms mentioned in the Accord are the foundation of creating a truly stable and lasting peace in Colombia. Many of the issues that cause conflict stem from the lack of positive state presence in the Colombian countryside in order to provide the infrastructure necessary for transportation, education, health care, and clean water. Much of this would be remedied by provisions in the Accord. Other provisions would provide a viable alternative to the cultivation of coca crops, so as to provide a continued income for rural farmers without contributing to the production of illicit crops.

Unfortunately, it is very unlikely that Duque will implement these aspects of the accord. The section on rural reform alone would take up about 85% of the cost of implementation for the entire Accord, something that would most likely be unpopular with Duque’s supporters. The majority, if not all, of Duque’s support comes from city dwellers and large landholders who benefit from the current status quo and would likely prefer to see resources allocated to urban projects rather than rural ones, as about 77% of all Colombians live in urban areas.

Furthermore, the Santos Administration never introduced the legislation that would be necessary to implement most of the rural reform seen in the Accord. Again, it is very unlikely these provisions will be included in Duque’s agenda, as it would require working against the interests of many of his strongest supporters.

Transitional Justice Mechanisms

In addition to his apathy towards to the rural reforms, Duque is also largely opposed to the transitional justice mechanisms introduced in the Accord, above all the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, which Duque has called a “monument to impunity.”

Duque wants to strengthen the punishments handed out to ex-FARC members, but will most likely be unable to do so, as the courts already approved the mechanisms and structure laid out in the Accord. Even if Duque were able to modify the punishments, it would be unlikely that the FARC members would accept any harsher punishments resembling those given to enemies defeated in battle, rather than through negotiated agreements as is the case for the FARC. Duque refuses to acknowledge the many atrocities carried out by the Colombian military during the long Civil War and never speaks of punishment for them.

Additionally, Duque has proposed Constitutional amendments banning amnesties for narcotrafficking, but these could not be applied retroactively and as such would only be able to be applied to future peace accords, not those involving the FARC.

Overall, it is unlikely Duque will carry out any of the provisions of the accord that are not specifically related to the FARC and their demobilization, effectively wasting one of the greatest opportunities Colombia has had to date to see truly meaningful efforts to create a stable and lasting peace.

As Adam Isacson of the Washington Office on Latin America said, “The FARC accord, especially its chapters on rural development, coca, victims, and political participation, offered an opportunity to make Colombia a modern, prosperous country.”

To ignore this accord for being “too lenient” on the FARC is frankly a disservice to the thousands of Colombians who have suffered for generations due to this conflict, and to the thousands more who will lose the opportunity to be the generation that undertook the necessary reforms to create a true and lasting peace in Colombia.