This year’s celebration will be hybrid. We will have a live online broadcast and we will also gather in person on Saturday September 17, so please mark your calendars. Learn more

This year’s celebration will be hybrid. We will have a live online broadcast and we will also gather in person on Saturday September 17, so please mark your calendars. Learn more

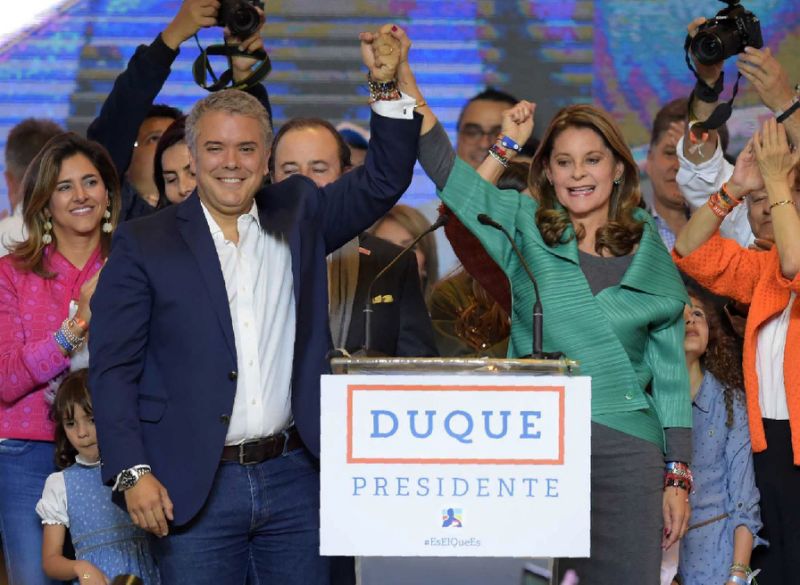

As someone who ran on a platform that was vehemently opposed to the Peace Accord agreed upon between Juan Manuel Santos and the FARC, Ivan Duque presents a challenge to the future of peace in Colombia.

It is unlikely that Duque will uphold or implement many of the aspects of the Peace Accord. The Constitutional Courts of Colombia have already reviewed the Peace Accord and made it clear that the Accord is law and must be upheld by the next three presidents, as the Accord envisions a 15-year implementation period. Despite this, it is still possible for Duque to take such slow measures in implementing the accord that there will be no progress at all during his presidency.

Although Duque has presented the Peace Accord as nothing more than a get-out-of-jail free card for ex-FARC members, in reality, the Accord offers a far-reaching opportunity for Colombia to develop into a more equitable and modern country. Many of the elements of the Accord focus on rural reform in the countryside and increasing educational opportunities and participation in government and politics among all Colombians.

While it is true that there are elements of the Accord that offer relatively lenient punishments to ex-combatants, such as the Special Jurisdiction for Peace that offers a means to avoid jail time, it is also true that this mechanism is largely responsible for preventing more than 7,000 combatants from disappearing and remobilizing.

The rural reforms mentioned in the Accord are the foundation of creating a truly stable and lasting peace in Colombia. Many of the issues that cause conflict stem from the lack of positive state presence in the Colombian countryside in order to provide the infrastructure necessary for transportation, education, health care, and clean water. Much of this would be remedied by provisions in the Accord. Other provisions would provide a viable alternative to the cultivation of coca crops, so as to provide a continued income for rural farmers without contributing to the production of illicit crops.

Unfortunately, it is very unlikely that Duque will implement these aspects of the accord. The section on rural reform alone would take up about 85% of the cost of implementation for the entire Accord, something that would most likely be unpopular with Duque’s supporters. The majority, if not all, of Duque’s support comes from city dwellers and large landholders who benefit from the current status quo and would likely prefer to see resources allocated to urban projects rather than rural ones, as about 77% of all Colombians live in urban areas.

Furthermore, the Santos Administration never introduced the legislation that would be necessary to implement most of the rural reform seen in the Accord. Again, it is very unlikely these provisions will be included in Duque’s agenda, as it would require working against the interests of many of his strongest supporters.

In addition to his apathy towards to the rural reforms, Duque is also largely opposed to the transitional justice mechanisms introduced in the Accord, above all the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, which Duque has called a “monument to impunity.”

Duque wants to strengthen the punishments handed out to ex-FARC members, but will most likely be unable to do so, as the courts already approved the mechanisms and structure laid out in the Accord. Even if Duque were able to modify the punishments, it would be unlikely that the FARC members would accept any harsher punishments resembling those given to enemies defeated in battle, rather than through negotiated agreements as is the case for the FARC. Duque refuses to acknowledge the many atrocities carried out by the Colombian military during the long Civil War and never speaks of punishment for them.

Additionally, Duque has proposed Constitutional amendments banning amnesties for narcotrafficking, but these could not be applied retroactively and as such would only be able to be applied to future peace accords, not those involving the FARC.

Overall, it is unlikely Duque will carry out any of the provisions of the accord that are not specifically related to the FARC and their demobilization, effectively wasting one of the greatest opportunities Colombia has had to date to see truly meaningful efforts to create a stable and lasting peace.

As Adam Isacson of the Washington Office on Latin America said, “The FARC accord, especially its chapters on rural development, coca, victims, and political participation, offered an opportunity to make Colombia a modern, prosperous country.”

To ignore this accord for being “too lenient” on the FARC is frankly a disservice to the thousands of Colombians who have suffered for generations due to this conflict, and to the thousands more who will lose the opportunity to be the generation that undertook the necessary reforms to create a true and lasting peace in Colombia.

As Colombia moves forward with a new administration led by President-elect Ivan Duque, marked by their aversion to the Peace Accord reached by former-president Juan Manuel Santos, the future of the Peace Accord is uncertain and other non-governmental entities have begun to pick up some of the pieces of the accord left abandoned.

The Presbyterian Church of Colombia has a considerably smaller presence than the Catholic Church, but focuses on more progressive approaches to many social problems. With a strong presence in Barranquilla, Urabá and Bogotá, and serving Afro-descendants, Indigenous and displaced persons, the Presbyterian Church has long been a proponent for peace.

Recently, CRLN was able to meet with representatives from the Presbyterian Church of Colombia and the Reformed University to discuss the current status of the peace process in Colombia, as well as the Church’s role in this process.

The Church’s main areas of involvement include: monitoring the implementation process; educating demobilized FARC members through the Reformed University; running reconciliation processes in communities and; providing leadership for DiPaz, an ecumenical group based out of Bogotá.

DiPaz has been involved in social processes and accompanying communities that work in building peace with justice through nonviolent action, the search for truth and justice that would allow for true reconciliation in Colombia.

Conversation focused on the current status of the Peace Accord in Colombia, which the representatives from the Church and University saw as shaky at best. They thought that the peace process would be unlikely to continue into the administration under Ivan Duque, and although that administration cannot legally do anything to end the accord, it seems likely that they will simply kill the initiatives through inaction.

One of the most controversial aspects of the Peace Accord is the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, known in Spanish as La Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz, and commonly referred to by its Spanish acronym as la JEP. La JEP was designed to exercise judicial functions and fulfill the duty of the Colombian state to “investigate, prosecute and sanction crimes committed in the context of and due to the armed conflict.”

La JEP offered amnesty for certain crimes in exchange for an admission of guilt from the perpetrators in order to facilitate some sort of reconciliation and transitional justice. However, not even state actors could unanimously declare support for this – the Colombian military supported la JEP, due to the ability to avoid any jail time, whereas former president Álvaro Uribe and his supporters, some of the most vocal opponents of the Peace Accord and its mandates, are strongly in opposition to la JEP as it requires an admission of government wrongdoing.

Due to the controversial nature of la JEP, it has progressed in its mandate much slower than planned. It seems that little will be done with the reconciliation aspect, especially under the new administration, and so the Presbyterian Church is working to pick up some of the pieces.

The Church is now working to carry out much of the reconciliation aspect, running reconciliation processes through the churches in local communities. These processes typically consist of a demobilized FARC member or Colombian military member coming to the Church and admitting guilt and asking those in the community for forgiveness.

In 2016, the Colombian government, under then-President Juan Manual Santos, reached an agreement for Peace with the long-standing rebel group FARC, whose acronym in Spanish stands for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia. Left out of this Accord, unfortunately, were the other major rebel group ELN and the paramilitary forces that often seemed to carry out atrocities with the tacit approval of the Colombian military. Atrocities against civilians were committed by all of these groups during the civil conflict in Colombia, which has been ongoing for the past 50+ years, despite multiple previous efforts to reach peace.

This accord was the first to include such broad citizen participation in the negotiation stage, which was held in Havana, Cuba, and included multiple representatives from civil society, including representation of Afro-Colombians, Indigenous persons and women.

Despite these high levels of involvement, when the Peace Agreement was put to a public vote in a plebiscite in the fall of 2016, Colombians voted No to peace by a 2% margin. The No camp was strongly led by former-president Alvaro Uribe, a prominent conservative, wealthy landowner and leader of the Democratic Center political party, who campaigned tirelessly to defeat the Peace Agreement. Many found the peace agreement to be too lenient towards the demobilized members, many of whom would see no jail time for the actions and would receive immediate seats in Congress. Others were swayed by conservative propaganda that alleged that one of the results of the Peace Agreement would be the institution of liberal sex education curricula in the schools.

The Colombian government considered the No camp’s qualms with the agreement and made some revisions accordingly, and the peace agreement passed the Colombian Congress later in 2016.

However, since that time, not much has really been done with the ambitious agreement. The agreement spans multiple issue areas and contains six main focus areas concerned with building a stable and lasting peace. These areas are:

Of these issue areas, only about half have seen any sort of marked effort for implementation, and even then not necessarily a full implementation. Illicit crops and their eradication have been a prominent topic, as well as the end of the conflict and means for reincorporation of demobilized FARC members into legal civilian life and areas regarding the victims of the conflict.

The section of the accord dedicated to illicit drugs offered many potential solutions for the eradication of crops made for illicit use as well as for the problem of illicit drug use, but neither have really arrived at a truly influential level of implementation.

Eradication of crops has been a slow process, as the fight between manual and aerial eradication continues. Proponents of manual eradication argue that it offers a more thorough and complete eradication of coca crops without spreading harmful herbicides over other crops and the communities, while also offering a more direct method of crop substitution and replanting of other, non-illicit crops. Those in favor of aerial eradication favor the increased efficiency of fumigation by planes or drones and claim that manual eradication is too slow of a process and also leaves open the possibility of resistance from growers.

The Peace Accord offered very explicit proposed solutions that all were centered on crop substitution and joint planning with the affected communities, but in reality it seems as if there has been very little direct involvement of the community growers. In particular, the Peace Accord contains an Ethnic Chapter mandating the direct involvement of Afro-descended and Indigenous community members in planning the implementation phase of the Accord, a stipulation that has so far not been honored.

Despite the government’s plans to eradicate coca crops, Colombia will never see true eradication until the government can offer viable alternative crops or some other means of livelihood to the rural growers. Without a guaranteed source of income, growers will never be willing to substitute their crops and the problem of illicit crops will continue.

The Peace Agreement’s focus on the end of the conflict and reincorporation for demobilized FARC members has most likely been the most effectively implemented portion of the accord.

The end of the conflict centered on the bilateral and definitive ceasefire and cessation of hostilities and laying down of arms. The laying down of arms was a UN monitored mission, as part of the tripartite Monitoring and Verification Mechanism comprised of the Colombian government, the UN and the FARC.

The UN mandate was to maintain a focused presence in areas heavily influenced by the FARC presence and was split into two distinct missions, with the first focused on the laying down of arms and the second as a verification mission. According to the UN, the ratio of weapons to combatants that were turned in was favorable, which is a good indicator of a successful disarmament.

The reincorporation process of the FARC into legal civilian and political life has proved both controversial and somewhat successful, although the government has not fulfilled all the promises of the agreement. The Peace Accord allowed for a section describing the political reincorporation of the FARC as a reorganized political party instead of a rebel group, with representation in Congress as well as funds for running and maintaining a political party.

The Peace Accord also offered a suggested allowance or financial support package for reincorporated FARC members to “start an individual or collective socially-productive project” as well as other economic and social benefits to members.

Although the FARC members have demobilized, many are still without resources or education, both of which were mentioned in the accord, and the lack of these resources have contributed to ongoing conflict in many areas.

The main point in the agreement regarding the victims of the conflict was the establishment of a Comprehensive System for Truth, Justice, Reparation and Non-Repetition. This system was designed to be made up of different judicial and extra-judicial mechanisms, with the following objectives:

The System also was designed with four main tenets:

There are six different mechanisms of the System as laid out in the Peace Agreement:

Of these six mechanisms, the most widely seen, and also perhaps the most controversial, is the Special Jurisdiction for Peace. The main reason for this controversy stems from the fact that the underlying principal of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (known by its acronym in Spanish as the JEP, or Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz), is a guarantee of amnesty and no requirement for serving any jail time for perpetrators of crimes that admit their wrongdoing and recognize their responsibility, in an attempt to facilitate reconciliation processes.

Many people find this to be too lenient on ex-guerillas as well as ex-military members, as it seems that many will choose to accept their responsibility in exchange for no jail time, but to many of the victims of the conflict this is not a severe enough punishment. The Accord claims that those who “decisively participated in the most serious and representative crimes and recognize their responsibility, will receive a sanction containing an effective restriction of their liberty for 5-8 years, in addition to the obligation to carry out public works and reparation efforts in the affected communities.”

Although the Accord also offers a detailed list of crimes that will not be the object of amnesty or pardon, such as crimes against humanity, genocide, serious war crimes, crimes of a sexual nature, extra-judicial executions, recruitment of minors, and other such serious crimes, many are still not pleased with what they see as a move that is more favorable towards the ex-FARC members and Colombian military members than to the victims.

With all this controversy, the JEP is not progressing as fast as had been intended, and under the new administration, it is uncertain what the future of this special jurisdiction will be.

The Truth, Coexistence and Non-Repetition Commission has taken some steps in terms of contributing to the historical clarification of what happened and promoting and contributing to the recognition of the victims. However, there is still much to be desired with many mechanisms of the Comprehensive System.

Overall, the Peace Accord has seen much less implementation than many had initially hoped. There has been little done in terms of comprehensive rural reform or implementation and verification mechanisms, and the items regarding political participation still have not seen much in terms of implementation. Voter turnout in Colombia remains low and very divided between urban and rural communities. Many conflict-heavy areas are still struggling, such as rural, Afro-descendent and Indigenous communities, despite the Peace Accord’s intent to involve them directly in decisions affecting their communities, an intent which so far has not been implemented.

May 2018 saw the election of Ivan Duque as Colombia’s new president, a staunch conservative and protégé of Alvaro Uribe. One of Duque’s main points during the election was his opposition to the current Peace Accord, something that worries the many proponents of peace in Colombia.

Although Duque cannot completely erase the existing Peace Accord, he can focus on only one part of it or move so slowly to implement it that much of the Accord will remain on paper alone. It remains to be seen if the segment of the Colombian public that wants to see the Peace Accord implemented can bring enough pressure to bear on the Duque administration to push him to do so more quickly and if the international community will be interested enough in the success of the Peace Accord to back them up.

For additional reading:

http://time.com/5297734/ivan-duque-colombia-election-risk-report/