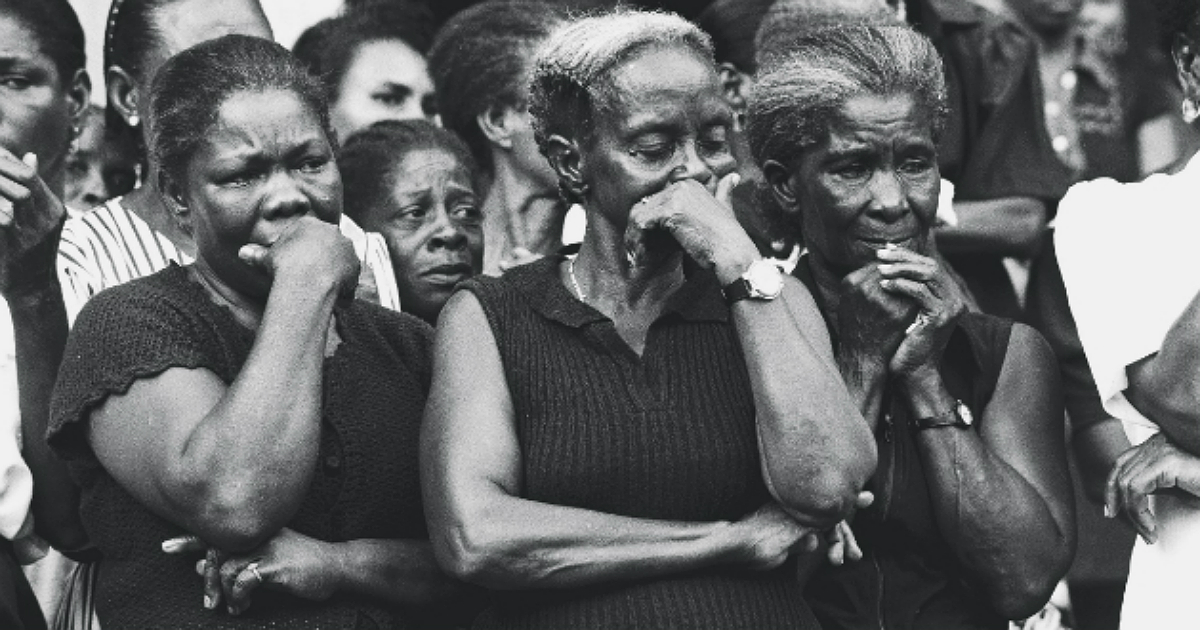

Face the Displaced

Colombia: Our Hemisphere’s Hidden Humanitarian Crisis

With over four million Colombians forcibly displaced from their homes by a debilitating war, Colombia is now the second worst internal displacement crisis in the world.

We would like to invite you, to help CRLN and people across the country do something about it.

On April 16-19, tens of thousands across the U.S. and Colombia will participate in this year’s Days of Prayer and Action for Colombia to call for a much-needed shift in U.S. policies toward the war-torn country. Please join us. Find out what you can do to by clicking “Read More.”

As you know,

the U.S. has for too long been part of Colombia’s problem, not the solution.

U.S. policy towards Colombia has been dominated by massive military aid, futile fumigations, and now a proposed NAFTA-style free trade agreement. In this moment of changing the way things are done in Washington, it’s our chance to call on President Obama to chart a new path with Colombia–one that halts the displacement, supports victims of violence, and opens avenues to peace.

To boost awareness of Colombia’s crisis and amplify the call for policy change, we are joining a dozen other national organizations in launching the fifth annual

Days of Prayer and Action for Colombia.

In March, hundreds of universities, faith communities, and organizations will be assembling thousands of printed faces of Colombia’s displaced people to be later displayed in poignant, eye-catching displays. While displaced people’s faces make appearances in numerous cities and towns in April, congregations across the country will be praying for peace in Colombia-focused worship services. The anticipated tens of thousands of participants will have the opportunity to send messages to the Obama Administration asking for policy changes needed to make peace in Colombia possible.

Here’s how you can get involved:

1.

Dedicate a worship service to Colombia in April.

On the weekend of

April 16-19,

hundreds of faith communities in the U.S. and Colombia will incorporate Colombia into the weekly worship service to raise awareness of the spiraling displacement andpray for peace. Please suggest to your faith community leaders this week that a worship service focuses on Colombia. We will provide you with a packet of sample sermons, prayers, background info, bulletin inserts, and other materials to help bring this critical Colombia focus.

2.

Host a “Face the Displaced” party in March.

Throughout the month, student, church, and community groups will be gathering to print and assemble thousands of faces of those currently displaced in Colombia. Through their portraits and accompanying statements, featured Colombians will tell participants the oft-tragic and oft-inspiring stories of their struggles to cope with displacement. Please ask your student club, church group, or community organization to consider doing a “Face the Displaced” party in March. We will provide you with a packet of faces, stories, instructions, factsheets, and other helpful materials.

Host your own event in March

or join CRLN and our Chicago partners for a workshop on

April 16th, 4-6pm at 8th Day Center for Justice.

3.

Display the displaced in a public demonstration in April.

Thousands of faces of Colombia’s displaced, upon being assembled in “Face the Displaced” parties, will be displayed in moving public demonstrations across the country in April. Please ask your student group, congregation, or community organization to consider setting up a public display. We will provide faces assembled in your area, in addition to tips on pulling off an effective display/demonstration. After April, the faces of the displaced will all be sent to Washington, D.C. for one final, massive display and to be presented in person to representatives of the Obama Administration. Join us at

Federal Plaza

on

April 19th, 11:30am-2pm

to raise awareness here in Chicago!

4. National Call in Day, April 19th.

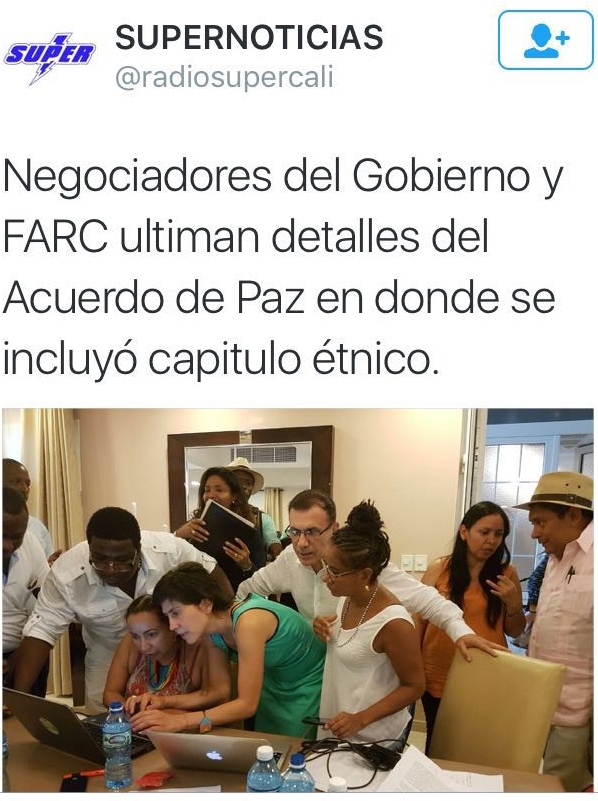

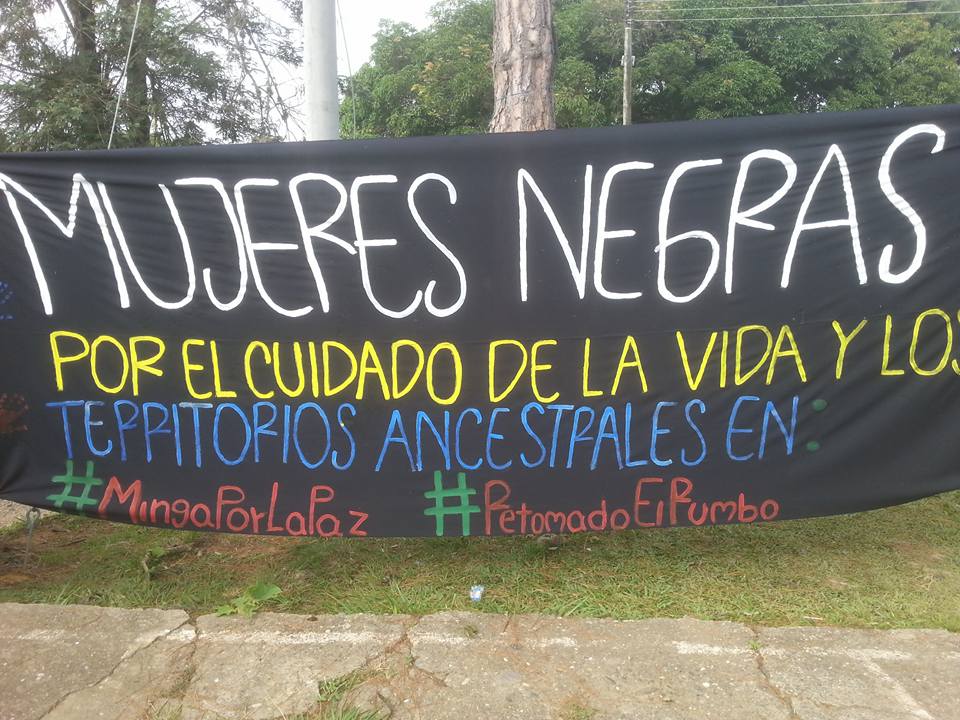

Join people all over the country in calling Congress to demand a new direction in US-Colombia foreign policy. We are especially asking our Members of Congress to co-sponsor

HRes 1224

, which protects the rights of Afro-Colombians and Indigenous peoples.

Click

here

for Witness for Peace’s Packet of instructions and resources for Days of Prayer and Action.

I hope you’ll consider standing with millions of displaced Colombians in this growing effort to bring meaningful U.S. policy change. Please let me know your thoughts. I am happy to provide the materials mentioned above and answer any questions you may have. Email me at

earmstrong@crln.org

for more information.