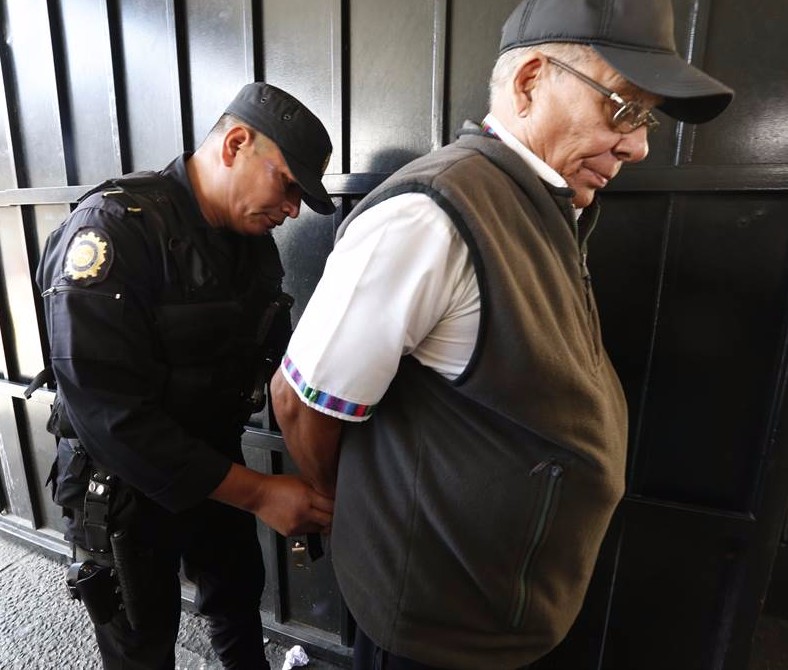

The recent arrests of 18 former Guatemalan military officers has set in motion the formal court proceedings of decades-long delay of justice involving countless human rights violations. The violations, during the country’s thirty-six year long civil war, took place between 1960 and 1996, officially “ending” with the signing of the 1996 Peace Accords. The corruption within the country’s infrastructure, however, is much more deeply rooted. So is the vast gulf between rich and poor, racism directed against the majority indigenous population, and the need for land reform, all issues that remain unresolved after the Peace Accords.

In a country of roughly 15 million, there are roughly

6,000 homicides within Guatemala each year, yet only 2% of those go to trial.

Additionally, the success of organized crime in perpetuating this violence–during the civil war and in recent years–has been possible in part because of government and military involvement in it. For example, former president Otto Pérez Molina, formerly a general during the civil war,

was arrested last year

just hours after his resignation from the presidency for accusations of corruption and fraud.

Now, Guatemala, desperate for social and political reform, has a new, democratically-elected President, former comedian and producer Jimmy Morales, a man who proudly boasted about his neophyte status with the campaign slogan, “Neither corrupt, nor a thief.” However, all of President Morales’ backers are military men. Will the violence lessen under him? He was elected, many think, on a “protest vote;” in other words, Guatemalans voted their distrust of the corruption of all political candidates who had any experience in what they see as a corrupt political system.

Morales has a full table in front of him with the trials coming up in his first year as president. One case, involving former dictator Efrain Rios Montt, has been delayed several times over allegations that

his physical and mental health are not well enough

for him to appear in court. Montt and former chief of military intelligence, Mauricio Rodriguez Sanchez, are now facing a retrial

charged with genocide and crimes against humanity

for their roles in relation to the deaths of 1,771 Mayan Ixiles between March 1982 and August 1983. In addition to Rios Montt and Rodriguez Sanchez, former Army Chief of Staff Benedicto Lucas Garcia, brother of former President Romeo Lucas Garcia,

faces charges

for crimes against humanity which took place during Romeo’s dictatorship between 1978 and 1982. In addition to Perez Molina, Rodriguez Sanchez, Rios Montt and Lucas Garcia, a host of other military officers from the School of the Americas–a combat training school for Latin American soldiers, specializing in counter-insurgency and teaching torture techniques–

were arrested for acts of genocide

, also taking place over 25 years ago.

What is next for the Guatemalan people, who demonstrated in the streets for 5 months last year to force the resignation of Perez Molina and to call for a better system of government? President Morales faces pressure from his military constituents as well as backlash from the anti-corruption, anti-fraud voters who put him in office. The steps he will take in response to the coming trials are nebulous. While the public largely supports prosecuting these criminals to the full extent of the law, his friends in the military have expectations that they will be found innocent and go free, or at the very least, that their trials will be delayed until these octogenarians die. As Jo-Marie Burt, a political science professor at George Mason University and senior fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America,

explains

, “This series of arrests from last week, some of them go right to the heart of the political allies that he has. I think that it’s kind of a little earthquake within Jimmy Morales’ inner circle.”

The importance of these court cases may be felt most deeply by the relatives of those lost during the thirty six year long war. After such a long time, it would be a huge emotional relief for the families of the victims of these military officers’ crimes if these violators were brought to justice. The government has repeatedly sought to deny that there was a genocide against the Mayan people. A guilty verdict would make the historical record clear and unequivocal. As Anselmo Roldán of the Association for Justice and Reconciliation said on the Rios Montt verdict, “To deny the sentence is to deny the value of lives lost. Each of those who died needlessly has value. The sentence is a recognition of that which was taken from us all.”